Nokia Bell Labs strengthens semantic communications research with KT collaboration

Nokia Bell Labs has been at the forefront of communications throughout its one-hundred-year history. Claude Shannon laid down the fundamentals of communications in his celebrated 1948 paper in the Bell System Technical journal that gave rise to the field of information theory and coding. Shannon also laid down the framework for lossless and lossy compression of data and developed the notions of entropy and rate-distortion theory. In their work, Shannon and his collaborators recognized that they were treating communication as an engineering problem focused on optimally transmitting symbols from source to destination, without addressing the meaning conveyed by those symbols.

Recently, however, there has been a major spike in interest to communicate meaning directly. Advances in AI and Gen AI tools are able to learn the underlying meaning and context from the symbols, which can also be exploited in the burgeoning field of ‘semantic communications’. Nokia Bell Labs is at forefront of this new field and we are collaborating with one of the most innovative service providers in Asia to drive research towards real world adoption.

Nokia Bell Labs and KT Corporation are partnering on joint research, design and validation of use-cases for semantic communications. The collaboration will include technical concept studies, evaluation and demonstrations that could potentially lead to the development of technologies for semantic communication.

What is semantic communication?

Semantic communication uses AI/ML to determine the minimum information to transmit based on the meaning of source data and its relevance for some goal at the destination, as well as any prior shared knowledge between source and destination. It has the potential to dramatically improve communication efficiency by focusing on the utility and effectiveness of the bits being transmitted, rather than just the raw data.

Figure 1. Illustration of semantic communication in the use case of identification.

Semantic communication is expected to enhance user experience and improve energy efficiency, particularly in the context of immersive communication and interaction within the future integrated physical and digital worlds. Additionally, 6G-era defining applications such as next-generation multimodal sensory communication, ultra-high-definition real-time holograms, remote healthcare and intelligent robotics will benefit from these advancements. The goal is to enable more intuitive and enriched user experience in the 6G era.

Research in the field of semantic communications covers multiple facets. Semantic compression refers to the process of compressing images, videos, or other sources of information to achieve a specific task, taking into account the context available at the receiver but not the communication channel itself. In contrast, joint source-channel coding (JSCC) involves compression schemes that also consider the specific characteristics of the communication channel, aiming to achieve lower latency or enhanced compression. When the network is made aware of the semantics of the information source through an application programming interface (API) or other interface, this is considered semantic networking. Information theoretic notions of ‘‘semantic entropy’’ and “semantic channel capacity” are still under active research, as universally accepted definitions have yet to be established. Below, we provide examples of some of these research directions.

Semantic networking framework

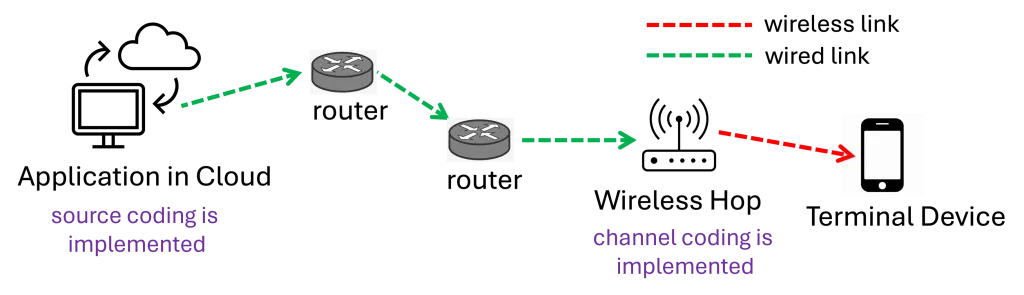

JSCC integrates source coding with channel coding, directly mapping each source message to a channel codeword. However, JSCC is impractical in existing communication networks, as illustrated in Figure 2. In these networks, application and network providers are typically separate entities connected over general-purpose TCP/IP links, where packets are either received perfectly or erased. With multiple wireline and wireless hops in between the source and the destination, the source encoder has limited and delayed knowledge about the wireless channel (usually the bottleneck), making it difficult to perform JSCC effectively.

Figure 2. Illustration of communication network with a mixture of wired and wireless links interfacing with packets.

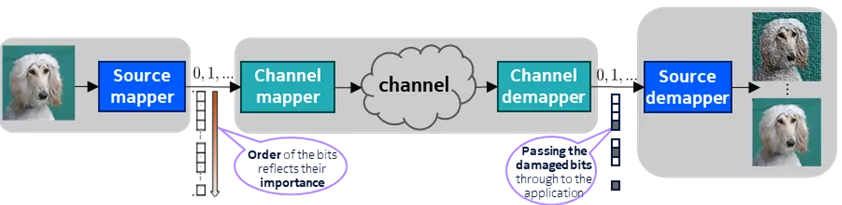

To address the interoperability challenge, we propose a semantic networking framework that conveys the underlying semantics of the message through an implicit interface from the source to the network, while also leveraging messages received over the network that are only partially correct. More specifically, we suggest a separate design of source and channel coding over an abstracted binary interface, as illustrated in Figure 3. In this design, the location of bits determines their relative importance, and erroneous packets are passed from the physical layer to the application layer. Furthermore, an in-network bit-puncturing scheme in conjunction with a rateless source mapper can adapt the transmission gracefully to varying channel quality.

By adopting this semantic networking framework, it is possible to achieve reduced latency with one-shot transmission even in the presence of noise and interference. This leads to lower end-to-end distortion and graceful degradation of quality adapted to channel conditions, without requiring the joint ownership of both application and network entities. This approach is particularly suited for scenarios that require low-latency and efficient image/video transmission, especially in long-haul or satellite networks.

Figure 3. illustration of the novel semantic networking framework allowing the separation of source and channel coding at different entities while maintaining majority of the benefits of JSCC.

In-network semantic compression

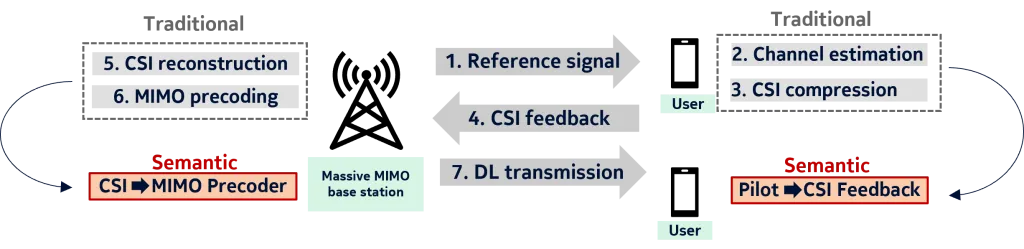

An example of a semantic-compression use case of high relevance to wireless networks is the in-network effective channel state information (CSI) feedback for massive MIMO precoding. Traditional MIMO systems require extensive CSI feedback to optimize downlink precoding, involving a chain of operation with multiple cascaded tasks, as shown in Figure 4. These tasks have their intermediate requirements that may not be necessary for achieving the end goal of optimizing downlink precoding, leading to significant overhead. However, by employing a semantic-communication approach, the system can derive CSI feedback tailored specifically for downlink sum rate maximization. This method significantly reduces the feedback overhead while maintaining high performance. Deep neural networks (DNNs) are utilized at both the user equipment (UE) and base station (BS) to map received pilots to feedback bits and feedback bits to precoding vectors, respectively. This end-to-end training, with tunable loss functions, allows for a controlled tradeoff, unlocking the full potential of massive MIMO systems.

Figure 4. Traditional chain of operation in massive MIMO CSI feedback and the semantic communication alternative.

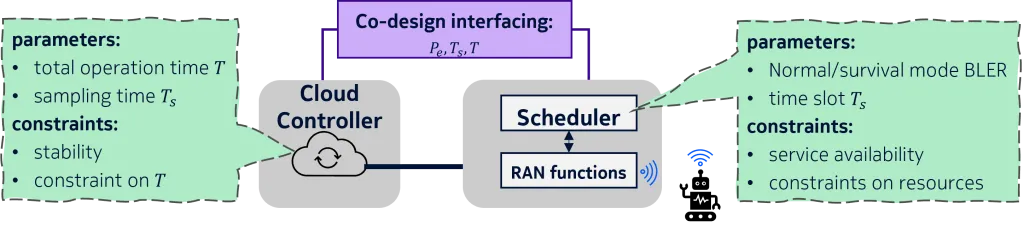

Controller-network interface for wireless industrial control

In industrial settings, semantic communication enabled by the semantic-networking framework can significantly improve the efficiency and reliability of wireless control systems. Through a new controller-network interface, as illustrated in Figure 5, control semantics can be conveyed to the network, achieving over 60% bandwidth reduction while maintaining service availability and stability. This is particularly important for remote-controlled robots and other industrial applications where timely and accurate communication is critical. The integration of semantic communication allows for better resource allocation and ensures that the most relevant information is transmitted reliably just in time, thereby enhancing the overall performance of the system.

Figure 5. Controller-Network interfacing and co-design for wireless industrial control.

Road ahead

In summary, semantic communication presents a transformative approach to wireless communication, enabling a wide range of advanced applications, from in-network CSI feedback to industrial control systems. However, there are many challenges that need to be addressed to make semantic communication a reality. For example, developing a scalable semantic metric to quantify the effectiveness of messages is essential to balance accuracy and complexity. The standardization of semantic interface and signaling is critical for ensuring interoperability. Additionally, addressing algorithm complexity, scalability, and robustness is key to successful implementation.

This partnership with KT marks the first publicly disclosed vendor-operator collaboration on semantic communication, aiming to validate feasibility and unlock new use cases for the technology. This initiative will test diverse use cases in realistic environments, laying the groundwork for a new communication paradigm in the hyper-connected era.