Meet Timo: The human story of the epic GSM project

Thirty years ago, in July 1991, the first official GSM call took place in Helsinki. It was a landmark three minutes – generating media coverage ever since. Yet this was just the tip of the iceberg. We meet Timo Ali-Vehmas, one of the “fathers” of modern networking, who worked away in the background to make it all happen.

The pavement outside the house has been ripped up and carted away in a succession of trucks. A vast oblong clay pit, filled with hard-hatted workmen, is fenced off where the street used to be. It’s noisy, inconvenient – but most traumatic of all – it’s playing havoc with the broadband.

Luckily the phone still works. So, with the help of a dongle and an awful lot of irritated grunting, it’s possible to connect the laptop to mobile broadband, log on to Teams, and speak to Timo Ali-Vehmas at his home in Kauniainen, Greater Helsinki, near Espoo in Finland.

Not so long ago the ability to harness superfast mobile 5G as a backup option would have seemed astonishing. Now, it’s like every other development in modern networking, where available it’s instantly taken for granted. Yet for all our entitlement, the technological excellence cannot be downplayed, and Ali-Vehmas is one of the “fathers” who made it all happen. Despite the pedigree, he’s very down-to-earth.

“I do not know if I fall into the category of ‘father of...’,” says Ali-Vehmas. “We were simply a bunch of young fellows eager to solve some problems.”

You could argue semantics on this sort of thing, but Ali-Vehmas was the original R&D project manager, responsible for the system design at Nokia on the very first official GSM call back in 1991. This was a big deal - one of the foundations of modern networking - and his role entailed building the project and the design to prototype, then taking these principles and applying them to all digital phones to come.

Since then, the GSM family of technologies have developed into a critical component of 3GPP standardization – the broad umbrella term for mobile standards – and been fundamental to global connectivity. This began with enabling seamless cross-border calling, then SMS, and now its latest evolution includes hosting mobile broadband and multimedia services.

“GSM is now used in 219 countries and territories serving more than five billion people and providing travelers with access to mobile services wherever they go,” says GSMA’s website.

The human side of groundbreaking technology

Ali-Vehmas is clearly passionate about his work. The room behind the camera is dominated by a floor-to-ceiling wooden bookcase with shelves of differing heights to accommodate the hodge-podge of different sized publications.

He punctuates his conversation by reaching behind him, or overhead, to pull out volume after volume to illustrate his point. Some are in English; some are in Finnish – many are very technical – and the lasting impression is of an impressive intellect.

“It was product development,” he explains about the period back in the late 1980s before the first GSMA call, “but there were other elements that needed to fit together too”.

The aim was ambitious: to unpack a technical blueprint and then get the chipset, software and phone all in one box. But the upshot was the first-of-a-kind innovation that eventually enabled the rollout of standardized calling, first in Europe and then around the world.

“It was difficult,” he says. “There were no examples as such.”

Together with a team of around 50 people by 1990, Ali-Vehmas describes a jam-packed but “very fun” daily schedule. Each morning everyone would look forward to solving now technical and human challenges, he says, describing an engineer’s dream of always having plenty of things to adapt, apply and test.

“Most of us were in a continuous ‘flow’ mental state,” he says, highlighting the working relationships between colleagues in Finland and collaborators in other parts of Europe, along with others in the US and Japan. This is worth remarking upon as it was long before the ubiquity of mobile phones, always-on internet, and today’s fully globalized world of Teams. This was precisely the world they were working to build, yet in a makeshift kind of way, they were living it.

The problem was, being in a continuous “flow” naturally came at a cost – especially with additional work demands. “This created a cognitive dissonance, and over time, it took its toll,” says Ali-Vehmas, explaining it was not a total burnout, “rather it was something like burning down – or running out of fuel.”

In the end, Ali-Vehmas took the project to the brink of completion – doing one last verification to confirm it was truly viable – then left to work on the TDMA phone for the US market. “The change in 1990 in my role was very good for me,” he says. “I had learned a lot, been solving so many problems, and seen even more solved by others.”

“This project was a marathon at the speed of 400m sprint.”

Helsinki at the center of the world

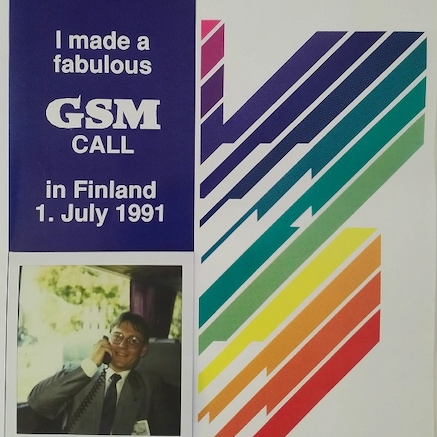

The official end of the race came on 1 July 1991 in Esplanade Park – a long strip of green in central Helsinki, which became a focal point for politicians, dignitaries and the world press.

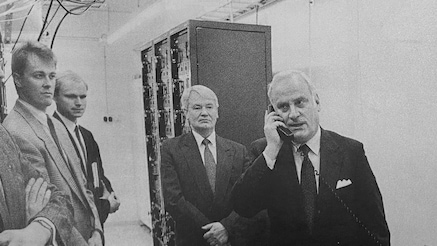

This was first official GSM call - the culmination of all that hard work - conducted on a car phone between then Finnish Prime Minister, Harri Holkeri and Kaarina Suonio, the Deputy Mayor of Tampere.

It was a very high-profile event, so much so that our own CEO, Pekka Lundmark – an account manager for Finnish GSM network operator, Radiolinja, at the time – conducted a test call to 100% confirm it was fit for debut.

Ali-Vehmas describes that afternoon as “like collecting the reward” and reaches across the Teams screen to proudly brandish a framed photo of the day. “This was the final proof that all the system-level decisions in 1988 and 1989 were right,” he says.

It was also a big day for Finland. A recent article in Forbes, “Tech Giants and Angry Birds: Why Finland Is The Place To Start A Company,”’ highlighted the Nordic nation’s leadership in innovation. And, in many, ways global recognition began right then.

“There are some characteristics in Finnish society that are very valuable in business,” suggests Ali-Vehmas, emphasizing strong trust, public openness and a drive to solve big challenges.

“Shallow hierarchy [and] leadership in front of the troops is overwhelmingly more valued in Finland than traditional management,” he says, adding this has been driven by the nation’s history and is vital to resilience.

Finland is, in fact, recognized for a number of qualities that build toward technological excellence such as equality across the board. While the unique concept of Sisu – which, despite no direct English translation encapsulates “perseverance and strength in the face of adversity” – is frequently used to explain national excellence.

In sport, Veikka Gustafsson became its national poster child by first being the first Finn to climb Mount Everest, then subsequently climbing all 14 of the world’s highest peaks without the need for extra oxygen. Yet there are many similarities between pinnacles in sport and tech.

Both require substantial work in the background to make them happen. Yet both are often enshrined in a few critical minutes at a summit, on a launch stage, or in a park.

Lessons from a tech pinnacle

The world we live in today is built on the legacy of a three-minute phone call. GSM calling was later adopted in the UK and across Europe, ushering in a new era of networking. Yet, like so many innovations, rollout was slow and halting at first until all of a sudden it took off and snowballed.

The year after the GSM call, the first commercial products were launched one by one on Finnish networks. It then took some time to get European roaming to work. All of that had been in the plan since 1987, but it wasn’t until 1994 that ordinary people started getting interested in GSM and then growth was phenomenal.

“It was far beyond our expectations,” says Ali-Vehmas. “When countries beyond the original set started to adopt the GSM technology, the global success story started to look unstoppable.”

Ali-Vehmas learned many things through the project, all of which informed his future work. These covered purely practical lessons, like how to build digital mobile radios and how a system design process should be defined. But more fundamentally he learned that “you must be careful who you choose to work with.”

“There must be a good combination of different types of people,” he says. “All of them must have world-class know-how – but this is not enough.” Everyone also needs to be united behind solving the same problem. Communication and trust within the team are paramount; competition may be necessary, but it must not hinder collaboration.

“It is funny that when we were building ‘networking technology with open interfaces’ we had to implement the same culture in our team. ‘Technical solutions’ are not the fundamental problem; the ‘people solutions’ are,” he says.

Like much of the industry, Ali-Vehmas continued to build his career on the bedrock of this critical project and kept on innovating. Over the last 30 years he has filed a number of patents, served as the chair of Nokia Foundation, and since retiring in 2020 has held a board position in the Finnish Museum of Technology along with the Executive in Residence position at the Aalto University in Espoo.

The events of this project are a lifetime ago for many - and ancient history in the wake of industry mega growth. Yet this is the absolute foundation on which it’s possible to speak to anyone, anywhere in the world, to hold a video meeting when the street cables have been smashed by maintenance, and where 5G and all the future generations of networking can thrive.

Even back in 1991, when the first official call was made, the vast backlog of work to get there felt like an old story. “I was working on other things already when the call was made,” says Ali-Vehmas “and in this sense, I was, if you like, in a ‘paternal’ position already.”