Regenerative Capitalism

Podcast episode 60

The convergence of digitalization and sustainability pays dividends. But according to Volans Ventures Founder, John Elkington, the key to a profitably sustainable future requires companies to change their views on capitalism.

Below is a transcript of this podcast. Some parts have been edited for clarity

Michael Hainsworth: To John Elkington, going carbon neutral isn’t enough. As the founder of Volans Ventures, he’s spent most of his career advising the corner office on how to go green sustainably – and ultimately become a force for good in society. He’s seen it all: through the 1970s where environmentalists were considered “dirty hippie communists”, through the digital revolution of big business in the 90s to where we stand today – on the edge of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Elkington believes we can leverage the digitalization of our world to make it a cleaner, better place and turn what he sees as the “degenerative” nature of capitalism into “Regenerative Capitalism”. But what does that mean, exactly?

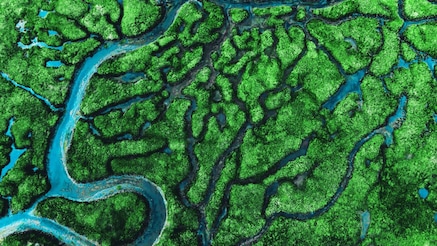

John Elkington: Well, in some ways, regenerative capitalism is an oxymoron. In a sense, capitalism has for much of its existence been a force that pushes particularly nature in the direction of degeneration. But there's no reason if we get pricing right, and price signals and so on, markets begin to operate in the right way that capitalism could not be regenerative. I think we're slightly distant from that desired outcome, but part of what interests us is experiments that are already happening in different places around the world, in different sectors of the economy, where people are trying to regenerate soils, trying to regenerate forests, trying to regenerate coral reef. But also communities and regional economies and national economies. So this isn't something that is just about nature. It's about economies. It's about our societies and communities. It is indeed about the natural environment and ideally all of that done in an integrated way.

MH: So if it's about activities that create the conditions for more life, rather than undermining it, on a recent podcast episode, we were told that the environmentalist is a CFO's best friend, because they're both focused on reducing waste. But how do we convince the CEO that sustainability must be part of the business model?

JE: One of the things that's happened in recent years is that firstly, when I started back in the late 1970s to engage business CEOs and other business leaders just simply did not want to hear about environmental issues, challenges, even opportunities. I mean, they saw environmentalists as effectively troublemakers, even communists. I think what's happened now is that the CEOs of some very, very significant companies with very extensive supply chains, so that they can leverage changes through those supply chains, have started to wake up to the fact that the climate is changing. Biodiversity is being lost. There are a range of different challenges which have risk profiles, which mean that they have to be taken seriously. So CFOs actually in recent years have become much more actively engaged in all of this. And I think that's just the beginning of a process. So I'm not saying that we have got where we wanted to be or need to be, but I do think we are seeing senior business leaders recognizing this is a grown up, sensible, critical issue increasingly for them to deal with.

MH: Are you suggesting that peer pressure is playing a role in convincing the CEO that sustainability must be part of the business model?

JE: Peer pressure's always been important. I remember back in the early nineties when we were trying to get companies to do non-financial or environmental or sustainability reporting. I had an anecdote, there was one of them about two CEOs swimming alongside each other in their club. And one of them talking about their new sustainability report and the other one feeling almost sudden in the moment naked, because he didn't have a sustainability report. That's a very sort of basic level of peer pressure. But I think it's now starting to operate in a rather different way.

And I signaled it a moment ago by saying very large companies are starting to switch on to a change agenda and not simply thinking about it within their own boundaries, but thinking about, and how do we cascade this through our value chains. And if a Walmart switches onto this as their CEO Doug McMillon did last year, and pledged then that Walmart would become a regenerative company, then anyone who wants to supply Walmart longer term really has to start thinking about what does that imply for their business models? Not just simply their reporting or their stakeholder engagement or whatever.

MH: I can imagine as well, as you talk about back in the 1970s, an environmentalist was akin to a communist in some quarters. I can imagine we've seen a turnover in that corner office and that churn has led to younger professionals with a desire to affect change.

JE: That's absolutely right. I mean, I think what's happened is that several generations in business terms, so not human generations of 30 plus years, but five, seven years or whatever have happened. And because of that, the people who are now on boards and in C-suites don't any longer see this as completely alien. They don't see this as something that is pushed upon them by people unlike them. They now have these priorities, these values themselves. Not everywhere in the world, but certainly in what we might call the global north and that is spreading.

Just again, a sort of anecdotal evidence. I've talked to a lot of CEOs in the last 18 months or so who have said something very similar to me as I'm getting this pressure now at the breakfast table, from my children. I'm getting this pressure from our interns, or I'm getting it from the talent that we're trying to recruit in to secure our future as a business. So they're not only younger themselves, but they're being forced to deal with the priorities of a rising generation and those are shifting quite profoundly and quite rapidly at the moment as we saw at COP 26, the climate summit.

MH: What role do digital tools play in going beyond net zero in creating this regenerative capitalism?

JE: Well, I think there are a few forms of technology and there are a few sort of sets of tools that are more important than digital technologies. And some of it's sort of over our heads in the sense that we absolutely depend now on satellite remote sensing. But as you come through supply chains, tracking of products, tracking of footprints and impacts and so on, we have to do so much more of that. And we have to also work out how to manage the unintended consequences of some of the solutions that we then put in place. Digital technologies are crucial. I think itself, it is often flawed. I mean, whether it's the surveillance society or facial recognition technologies and so on, we all know the problems that have been bubbling up in that place. Partly because a lot of the coding, the design, is done by people who happen to be young, white and male.

And I think these are teething problems. I'm sure we will come through them. But when I look at some of the very big systemic solutions that are starting to engage now, for example, electric vehicles, and you start to think about electric vehicles basically as computers on wheels and you think about the smart grids into which they then will plug. I mean, that's the digital economy in spades. So, we can no longer think about these things as disparate, separated, unrelated. They are absolutely joined at the hip and increasingly will become the same thing.

MH: The fourth industrial revolution is here. Manufacturing is one of the greatest contributors to greenhouse gases, more than 16 gigatons of CO2 per year. What role does 5G and the Internet of Things play in regenerative capitalism on the factory floor?

JE: Well, I think one of the places that regenerative capitalism has to strike root is in the world cities. I mean, that's where the bulk of our species now lives. And it'll go up to something like 70% within a couple of decades. So if regenerative capitalism and the regenerative economy is to mean anything, it's really got to shape the way that we design, the way that we build, the way that we operate and the way that we value our built environments and the infrastructures that they depend on. So increasing rates of information transfer and the security of the infrastructure that achieves that, because we all know cyber hacking is increasing a problem. I remember probably 10 plus years ago, going to Portland, Oregon and visiting part of Intel and talking to the woman who ran what they called their security fabric division.

And she was saying at that time, 40% of digitally connected buildings were being hacked every year in the United States. And I'm sure that's not got better since then. In fact, I think the scale of some of the intrusions has increased quite considerably. And when you think about that, that's almost in the realm, again, of unintended consequences. Because we're wiring our buildings, we're wiring our infrastructures and our cities with the best intent, but not always thinking about what happens if for whatever reason, it could be accidental, it could be deliberate, those networks go down.

What then happens? Not on only in terms of loss of life, human life, but in terms of the knock on effects in terms of pollution and other things. So I think digital technology is absolutely make or break, but we've got to get the right technology in the right sort of way. So 5G and Internet of Things, absolutely fundamental. And I'm quite pleased because I think the sustainability movement, the sustainability industry in a way has been working much more intensively in recent years with this sector and with companies like Nokia, because I think that they too see that this is make or break for them as well.

MH: Do you see any sense of optimism or success stories tied to that Internet of Things, Industry 4.0 view?

JE: I think many of the people who've developed the fourth industrial revolution sort of agenda, almost mindset, see this as an innately positive set of developments. Most of these technologies have the capacity to reduce environmental footprint of business activity by 90 plus percent. So I mean, that's incredibly valuable if we can get those sorts of improvements. But again, each technology brings with it a range of impacts. Most of them are often positive socially, environmentally and the rest of it, but they will also bring things that we didn't expect. And one of the things that slightly alarms me sometimes is that as in every previous industrial revolution, there is a race to market. And we very often find out about the unexpected consequences a bit late in the day.

I think things have changed. And I am optimistic in the sense that I think most of the big IT companies, telecommunication companies and so on, are much more sensitive to these issues than they once would've been. Partly, that's a generational shift, but it's also, they've had problems along the way. And most of them have learned some quite consequential lessons from all of that. So we're much better prepared, I think, than we might once have been. But the pace and scale now of the digitalization or digitization of the global economy is going to be so ferocious that the sort of interference effects between some of these technology is going to be fascinating to behold and quite problematic at times then to sort of clean up after the event.

MH: Transportation, from personal cars to freightliners, just another major contributor of greenhouse gas emissions, needs to be lowered by as much as four and a half gigatons over the next 10 years. What role does mobile connectivity play in regenerative capitalism in this space?

JE: Well, particularly in transportation of mobility, there is a group based both in Silicon Valley and in the UK called RethinkX. And they've done a series of sector studies and the first one they did about three years ago looked exactly at this space of transportation and mobility. And what they projected then was that by the early 2030s, we would see something like a 50% increase in kilometers or miles traveled. But at the same time, we'd see something like a 70% decline in the revenues earned in the process. If you're an automobile or a trucking company, or an oil company, all of that, even if it's sort of off by sort of five or 10 years, is going to have massive consequences. The thing about these industries is that they're connected in ways that would be very difficult to have imagined 10, 15 years ago. Some people did, but most of us didn't. And again, if you push the time scale out another 10 to 15 years, absolute extraordinary level of evolution. And I think connectivity is going to be absolutely central to that.

And then the question is, when we're already overwhelmed by incoming data and information and so on, how as a species, how as industries, how as companies, how do we make sense of all of that? And that's where, I think, we've seen big data, we've seen expert systems, we've started to see growing interest in artificial intelligence. And my own sense is that none of this is going to work long term at the scale and in the ways that we need it to work, unless we can develop AI in the appropriate way. So I've been paying a lot of attention to that sector, visiting people like DeepMind, some of the people who are sort of developing some of these absolutely critical technologies. So connectivity, absolutely core, but it's got to be done in the right ways.

MH: A global switch to solar and wind could cut CO2 emissions by a combined 4.1 gigatons. Is this how we make energy production and distribution regenerative under capitalism?

JE: Well, one of the dangers about the regenerative tag or branding is that in the same way that people try to stick sustainable or circular onto everything that moved, we're going to see a lot of people trying to apply that sort of tag to things. For example, like the evolution of the energy sector. Now, I think it's regenerative if we move towards a solar, wind, battery future and where those technologies improve exponentially and their cost points come down exponentially as well. But the question of whether that's regenerative depends on exactly how those energy sources are designed and positioned and so on. To take a stupid example, but for example, you're putting windmills in the migratory paths of large birds and they're being sort of stunned or killed along way. That's not a part of regenerative strategy. So that in a way, as you said earlier on, regeneration is about life creating the conditions for more life.

And I think if the answer to your question is that the people who are driving this energy transition have that in mind and are delivering outcomes that move in that direction, yes, that's towards regenerative and the same way we might say it's towards circular economy outcomes or whatever. But it's not guaranteed. It depends on us, it depends on us as investors and technologists and business leaders and so on. But my optimism comes from the fact that I think increasingly most of us do sense that this is the emergent reality, that we're going to have to operate in a very different form of normal going forward. And as a species, we tend to do our best work when we've either been backed or backed ourselves into a corner. And here we are in a way in the mother of all corners.

MH: One requirement of regenerative capitalism is that companies embed sustainability as that integral part of the strategy. What role does the culture and values of individuals driving this change towards shared values and new business models play?

JE: It's a critical question, thank you. And I've been on, in just the last couple of days, on a series of calls with people who are developing new standards around sustainability, working on the regulation of different industries in terms of sustainability and so on. And all of that's essential and all of that is potentially going to drive things along relatively quickly over time. But in the end, so much of this depends on us as human beings and the values that we embrace, the priorities that we have, the sort of commitments that we make, the targets that we set.

And so I think the concept of regeneration, it's immensely powerful because it isn't doing a less harm formulation. It's saying, over time, it's not good enough to just push towards net zero, shrinking your negative impact. We've all got to think about how we rebuild communities, how we rebuild regional economies, how we rebuild the biosphere over that time, and no individual company can do this on its own. So again, this is going to require very, very close collaboration, not just between different businesses and different industries, but between different sectors of society. And partnership has often been talked about over the last 20 years in this field, the nature of the partnerships, the scale of the partnerships that we now need to develop on a very different scale indeed.

MH: With my tongue firmly planted in my cheek, let me ask you this. Did you ever think, back in the 1970s, that you'd be this tree hugging communist advising the world's largest companies on eliminating their carbon footprint?

JE: In the 1970s? Yeah, because I set up a company with several other people in 1978 to open up business to start talking about issues that it really didn't want to talk about. Like safety, health, environment, these sorts of things. But to your question, would I have then thought that I would move into the sort of global boardroom in the way that has happened subsequently? It might have been on the wishlist, but it wouldn't have seemed like a realistic prospect. And then I wrote my first report on climate change back in 1978. And at the time, when I think back to that moment, I thought things would in many ways go much faster than they have. But one of the books that had amazing influence on my own thinking was Thomas Kuhn's, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, came out in the early sixties.

I read it when I was 14, back in the early sixties and have kept going back to it because I keep disbelieving what I remember from it. And one of the things I remember was that he made the point that these very big fundamental paradigm shifts, a notion that he introduced, take something like 70 to 80 years to work their way through. Well, if you think about the late fifties, early sixties, that's when environmentalism started to take off. The NASA shots of the earth from the outside. We're 65 and counting years into that paradigm shift.

What Kuhn also said, towards the end of a shift, you go through a series of inflection points and the pace of travel increases to an extraordinary degree. Doesn't mean you go in the right direction, but the energy released is extraordinary. That's where I think we now are. And so, no, I couldn't have foreseen it happening. I thought we'd go in more of a straight line trajectory. We're sensible people, we'd address these challenges. We've delayed it for so long that we've put ourselves in a gradually then suddenly world, as some people call it, where things teeter along for quite long time, and then boom, they go somewhere else.

MH: So many of these goals are for 2050. Neither you nor I are going to be around by 2050, but the wise man is the one who plants a tree for shade he will not enjoy. Are you confident in the seeds being planted today for a sustainable future?

JE: To be absolutely clinically honest, no. Because I look at, I mean, my favorite subjects at school were things like history and archeology and both of those disciplines show that pretty much every civilization to date has collapsed. And they've typically collapsed for one of a number of reasons. One of the critical areas has been overstressing of the local environment for resource and so on. So I think it's much more likely now that our civilization will go where most of us really don't expect.

At the same time, because I think we've backed ourselves into that existential corner, the potential for getting people to do things, to think things and do things that they would not have been able to imagine a short while ago, I think it's also increased very powerfully indeed. So I'm often asked, am I an optimist or a pessimist? And I find it a difficult question to ask, but in terms of the question you just asked, Michael, I think I see this as the critical point in our evolution as a species. And particularly since the industrial revolution. We have a chance we have an opportunity. Young people are rooting for us to do it. Question is, can we? I'm committed to doing my absolute damndest over the next 10 to 15 years to making it happen. But do I have a deep, deep sublime confidence that we'll do it? No, not really.

MH: Well, I'm so glad we could end this conversation on an up note.

John Elkington: (chuckles)